Dreaming has fascinated philosophers, psychologists, and neuroscientists for centuries. We drift into these surreal experiences, where everyday logic can dissolve, yet we feel present and alive in alternate realities. As Freud once thought, many people believe dreams carry hidden messages in our own subconsciousness. While interpretations vary across cultures and times, we can take a scientific perspective by examining how the brain’s complex networks might activate and coordinate to generate our dreams.

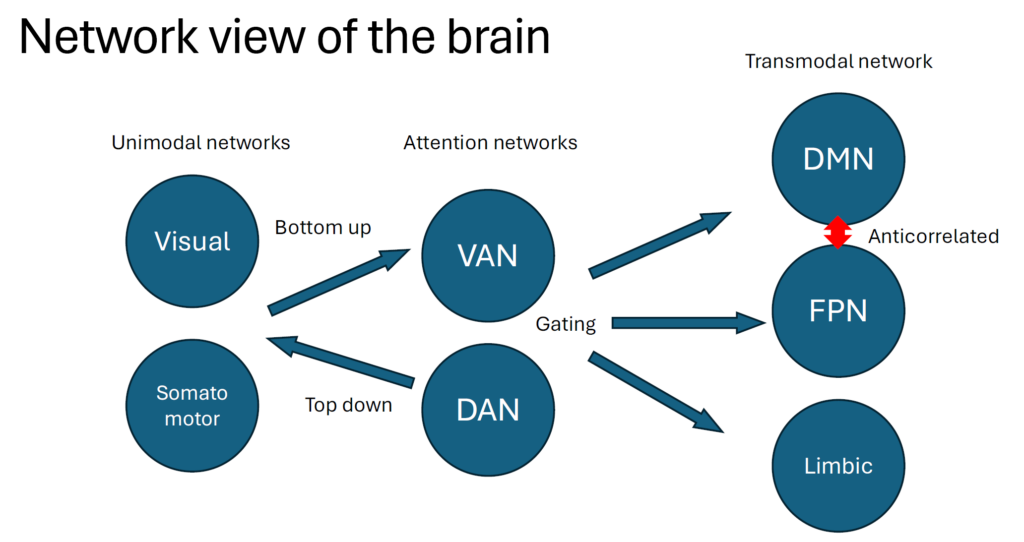

In one of the prominent consciousness theories, the Global Neuronal Workspace Theory (GNWT), consciousness arises from the integration and broadcasting of information across widespread neural networks. During typical waking states, specific information wins a competition for neuronal resources, gains prominence, and is then broadcast to various areas responsible for language, decision-making, and so forth. This neural “workspace” is a key place of convergence, making certain information globally available and thus consciously experienced.

Dreams, from this standpoint, can be viewed as arising when the brain’s sensory input is mostly decoupled from the external world (you’re asleep and your eyes and ears aren’t relaying nearly as much data), and internally generated imagery or memories now gain stronger access to this global neuronal broadcasting mechanism.

Yet dreaming isn’t simply a random collage of old experiences. It’s shaped by the rhythms and neurochemistry of the sleeping brain. Brain structures that mediate emotion, such as the limbic system, become highly active, while “higher-order” areas for logic or self-reflection can be relatively down-regulated. According to GNWT, even though external sensory input is minimal, certain internally generated states can still be forcefully “broadcast,” filling the workspace and thereby producing the rich, immersive, sometimes emotional experience we identify as a dream. This means that a single fragment of a memory, fear, or wish might gain temporary dominance in the global workspace and weave together to create some narratives.

So, how should we interpret these nighttime stories in a GNWT framework? In essence, dreams reflect the brain’s tendency to produce globally available images and emotions, but in the absence of constraints from external reality. They are thus illusions that leverage still-real components (memories, insecurities, and desires) reorganized in unpredictable ways. It doesn’t diminish the potential emotional significance of dreams, but it does cast them in a new light: as a phenomenon that results from the dynamic interplay of neural systems fighting to broadcast their internal content to the global workspace, now freed from external stimuli.

It should be noted, however, that peer-reviewed research explicitly connecting dreaming to GNWT is quite rare, in part because GNWT was devised to address “access consciousness.” Access consciousness refers to the kind of consciousness that is available for verbal report, reasoning, and action control (which is mostly impossible during sleep). Nonetheless, dreaming provides a vivid case study of how subjective experience emerges even when external inputs are minimal. This makes dream experiences a valuable test bed for theories of consciousness, offering an unusual but compelling look into the manifold ways our brains generate and sustain phenomenally rich states of mind.